The Promise of Six Sigma – A rationale approach for process improvement in industry delivery

By Ian R. Lazarus, FACHE and Keith Butler, M.D.

(This article is presented in two parts. Part One introduces the concept of Six Sigma and its application in a variety of industry environments. Part Two follows certain projects through to conclusion while providing more advanced concepts to those considering the application of six sigma principles at their organization.)

It took a master of merchandising to make it happen, but statistical analysis applied to business improvement is now the most demanded form of industrial change management. Thanks to GE, a process known as Six Sigma is making its way from the manufacturing sector to the services industries. And industry delivery is not far behind.

The inescapable appeal of Six Sigma lies in a wholesome concept: numbers don’t lie, and inevitably, they reveal the underlying “physics” of an operating system. In other words, data-driven process improvement, which lies at the heart of any Six Sigma project, is reliable, defensible, and practical. The ultimate promise of Six Sigma is to reveal the proper interpretation of data, leading to better decisions. The goal: using customer-driven outcomes to “get better faster,” in a marketplace where customer loyalty takes on growing importance.

The story of sigma.

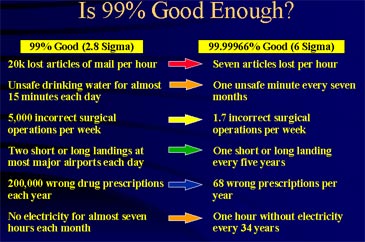

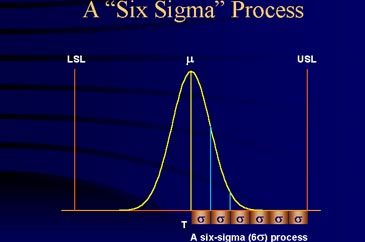

“Six Sigma” has come to mean different things to different people because the core concept has diversified to become a philosophy, a belief system, and a disciplined process for rapid improvement. Simply put, “sigma” is the 18th letter of the greek alphabet; it is also the statistical symbol for standard deviation. The fundamental objective of Six Sigma is to use data to reveal defects in procedures, to ultimately operate within six standard deviations of average performance, and to employ customer-driven measures in establishing the target for ideal performance. Once achieved, the organization is operating at a level that is “defective” only .0003% of the time. Too ambitious? Consider the implications of anything less, illustrated below.

A place in history.

It’s hard to argue with the logic of Six Sigma principles, and even harder to ignore its potential when looking back on its contribution to industry and society. The use of statistical analysis to improve production yield dates back to pre-industrial times, when agricultural societies used statistics to improve the yield from crop production. The fact that we have an exponentially greater population with a much lower percentage of people working in agriculture is a visible example of how improved production techniques dramatically impact yield. In the industry industry, the use of statistics has traditionally been focused on looking back at production values, but not necessarily developing new models of production going forward.

Six Sigma concepts came together with greater visibility immediately after WWII, when the Japanese auto industry used the only method possible to compete against an established auto industry in the U.S – a relentless focus on better quality. The Toyota Production System gave an entirely new meaning to the phrase “made in Japan,” and forced the American auto industry to adopt similar principles. It did not take long for Ford Motor Company, Motorola (a supplier to Ford), and eventually General Electric to adapt Six Sigma principles and to incorporate them into the very fabric of the corporate culture.

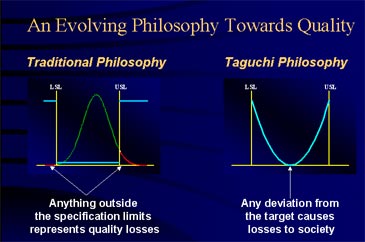

One of the major contributions of Six Sigma is a reorientation to the definition of what constitutes “acceptable quality.” The impact of consumerism is accelerating a return to traditional values in how quality is defined, with an emphasis on customer-driven measures. The once familiar “goalpost mentality,” that is, ensuring operations conform to upper and lower targets, is being replaced by the “bullseye” philosophy that any deviation from the customer-defined target represents a corresponding “loss to society.”

The culture of Six Sigma.

The vernacular of Six Sigma may cause the casual observer to think they have tapped into a new cult. Worse than this, calculations of “rolled throughput yield,” “defects per million opportunities” and “sigma level” might intimidate managers without adequate training in analytical statistics. It’s important to note that Six Sigma represents a series of analytical tools, and the practitioner’s role is to apply the proper tool to address the problem, just as the surgeon must select the proper instrument to treat the patient. In this regard, Six Sigma training is necessarily rigorous and demanding, and finding qualified practitioners is key to a positive experience with the methodologies.

Most industry organizations begin Six Sigma projects with outside consultants to introduce them to the concepts and potential impact on operations. Ultimately, a more permanent approach will be to train dedicated personnel in the organization to undertake future Six Sigma projects. Fully trained practitioners are referred to as “Six Sigma Black Belts,” and those designated to work in a supportive role are “Green Belts.”

The practitioner’s ultimate goal in any Six Sigma project is to define the functional characteristics of a defective process. They arrive at this by examining the underlying physics of one operating system at a time: the emergency department, operating suite, billing office, etc. The process used to determine these relationships follows a consistent path:

- Define the problem

- Measure the problem

- Analyze the data

- Improve the system

- Control and sustain the improvement

Defining the problem involves determining “defects” in procedures: long cycle times, high costs of operation, redundant or reworked processes. Various tools are used to validate the impact of defects and possible improvements, followed by small scale experiments to establish the ultimate solution. The projects often also employ streamlining techniques (getting “Lean”) to improve productivity and workflow.

From the back office….

During the summer of 2000, Mount Carmel Health (Columbus OH) reflected on a year that was less than spectacular. Net income from operations fell so low the organization barely broke even. The organization was forced to eliminate 200 positions, about half of them with personnel already in place. Employee turnover and satisfaction were at all-time lows. And the situation for competition around them was equally bleak. The leadership was determined to avoid future layoffs and another year of poor financial performance.

Chief Executive Officer Joe Calvaruso, together with other members of senior management, examined the potential of Six Sigma and initiated a plan to implement the methodology. A full-scale deployment, one of the first-ever in industry, soon followed. Today, 44 executives at Mount Carmel have been trained in the principles of Six Sigma, 52 projects are in different phases of implementation (10 more are expected by the time this article is published) and 5 projects are in the “realization stage” (completed and subject to ongoing monitoring).

Mount Carmel’s commitment to Six Sigma goes beyond a belief in the potential benefits from the process; the organization has ensured that all employees engaged in Six Sigma projects will be offered alternative positions if, as a result of the project, their duties are eliminated. More significantly, the organization requires any newly trained Six Sigma professional to permanently leave their position in order to focus exclusively on project deployment, and positions vacated must be back-filled with existing personnel.

One of Mount Carmel’s first Six Sigma projects was focused on a simple, common problem: timely and accurate reimbursement. They discovered that their Medicare Choice product was writing off huge amounts as uncollectable due to HCFA denials. The organization did not expect the business line to be extremely profitable, leading to a certain ambivalence toward the uncollectable amounts. However, a Six Sigma process revealed that the problem lie simply in the coding of reports submitted to HCFA, more specifically around the status of patients classified as “working aged.” Since the status of these patients often changed during the treatment process (with regard to work status), HCFA either rejected claims or did not reimburse fully for the care. Original estimates from fixing the problem: a $300,000 gain in net income. Actual “realized” amount: $857,000. It appears that as a result of improving the coding process around one parameter, the organization improved reporting among many other parameters as well, dramatically boosting revenue collection.

…to the front lines

Virtua Health is a nonprofit integrated delivery system anchored by four hospitals in the Southern New Jersey/Philadelphia market. In early 2000, management launched the ‘Star Initiative,’ focused on achieving milestones in clinical quality, patient satisfaction and financial performance. Walter Ettinger, MD, Executive Vice President at Virtua, is responsible for the implementation of Six Sigma as a strategy to achieve these goals. The organization has trained six black belts and over sixty part time coaches; together they lead projects using the Six Sigma methodologies. The organization has undertaken projects in nearly every aspect of its business.

At Virtua, the most common admission for adults over 65 is due to exacerbations from CHF. The Six Sigma project team found that outcomes, length of hospital stay, and treatment pathways were highly variable. They expected a correlation between length of stay and case acuity, but such a relationship was not evident from the statistical analysis. By using Six Sigma to define the causes of these variations, the team designed solutions that involve patients and families in the delivery of care, and they also streamlined the overall process. Virtua was able to realize significant improvements in the quality of patient care and a significant decline in the length of stay.

Ettinger reports that the organization has been very pleased with the results of these and other Six Sigma projects. He emphasizes that an organization must maintain a long-term focus on results from project opportunities. At Virtua, the focus is on improving the patient’s experience, workflow improvement and productivity. By improving these areas, Ettinger suggests, bottom line improvement will follow.

Natural Laws.

It could be argued that a properly executed Six Sigma project is as defensible as the laws of nature. You cannot deny the underlying physics of a system any more than you can deny the existence of gravity. The only remaining issue, therefore, it what you plan to do about it.

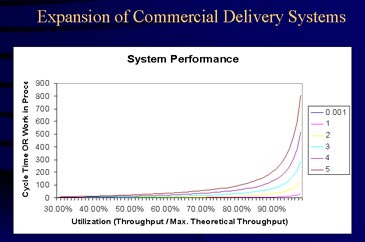

A powerful demonstration to this can be found in “Little’s Law,” sometimes referred to as the first fundamental law of system behavior. The law demonstrates the exponential rise in “cycle time” when more and more inputs enter the system. When the system nears full capacity, cycle time approaches infinity. Anyone who has seen patients waiting on stretchers in the Emergency Department has witnessed a natural byproduct of this law.

Further challenging administrators dealing with the affect of Little’s Law is two key forms of variation: arrival variation (that is, not having control over the arrival of some patients), and process variation (different people doing the same things differently). Variation causes inefficiency; it is the enemy of best practices. When process variation is high, the curve jumps forward, causing productivity to fall as cycle times rise. To combat this, some providers artificially reduce demand by closing their doors (called “diversion” in the ED). The demand still exists, but the organization simply cannot accommodate it. Such a reaction is commonly referred to as “squeezing the balloon.” A more sensible approach, one advocated by Six Sigma practitioners, is to reduce process variation, improve the yield from the system, and jump back down to the lower curve on the graph. From here the organization can capitalize on gains by increasing production, lowering cycle times, or both.

Supply vs demand.

The city of Scottsdale (AZ) is home to thousands of “snow birds” which flock to the resort destination each winter in search of warmer climates. Snow birds have residence in Arizona during most of the winter months, which coincides with flu season affecting both visitors and permanent residents.

The dynamic of supply versus demand in emergency services may be more evident here than in most U.S. markets. During the first six months of this year, hospitals reported over 12,000 hours during which they closed their doors to new patients and advised ambulance services they entered “diversion” status; that is, officially unable to accept new patients via ambulance. Scottsdale’s experience reflects a growing national phenomenon, largely because there are fewer EDs (4945 in 1997 compared to 5210 in 1988) absorbing a higher number of visits (104 million visits in 1999 compared to 81 million in 1988).

One of the city’s busiest trauma centers operates at Scottsdale industry’s Osborn campus. ED visits at the hospital are up 7.6% from the prior year and 13.8% in the past two years. The hospital’s own diversion rate has climbed 74% in one year and patients leaving the ED voluntarily (before being seen) had skyrocketed 272%. Patients leaving before being seen reflect a level of dissatisfaction with the availability of services; those that did remain long enough to be seen reported satisfaction levels lower than any other department. The hospital estimates that it can lose as much as $500,000 each quarter that this condition persists.

SHC already has plans to build a replacement facility to boost the capacity (“supply”) of the ED in anticipation of growing demand. They are also examining new ED models of care to more efficiently handle the growth. Management recognizes bottlenecks and delays in treating patients within the current facility that would carry over into the new facility, if not eliminated first. The organization is determined to build a “world class” operation, not just a larger facility with the same operational challenges.

Enter Six Sigma: Consultants mapping the ED process detected three possible “defects” causing bottlenecks so significant that they have a direct impact on the hospital’s probability of invoking a “diversionary” status: registration, lab/radiology turnaround, and transfer to inpatient beds when patients require admission. Further analysis revealed that average time to transfer a patient out of the department is 80 minutes, but for fully half this time the inpatient bed is actually ready and waiting. The hospital is now in the process of implementing improvements to their “bed control” process. Procedure changes designed into the existing facility will help establish the potential capacity of the new facility, and will allow staff to gain comfort with new procedures before transferring to a new physical environment.

“Not your father’s TQM.”

Critics of Six Sigma will argue this is just another passing fad or the return of Total Quality Management/Continuous Quality Improvement (TQM/CQI) techniques under another label. Such a reaction is natural when the underlying differences are not well understood.

In fact, Six Sigma tools work effectively in concert with long term efforts at quality improvement, but this is where the similarity ends. Six Sigma is by definition a short term solution to long term problems, it cuts across department lines, is driven by senior management, and has a narrow focus but very significant impact on the organization’s profitability. Efforts driven by TQM/CQI solutions, on the other hand, are typically “grass roots,” ongoing initiatives where incremental change delivers incremental benefit. In TQM/CQI initiatives, the use of statistical analysis focuses on controlling the process, rather than disrupting it. In spite of these key differences, it should be emphasized that the teams devoted to each discipline must work together, with market forces determining the urgency for one solution over the other.

Still stuck on semantics? Consider this perspective from an authority on industry operations improvement, Andrew Pattullo Collegiate Professor John R. Griffith at The University of Michigan. Griffith has studied industry operations improvement for nearly 30 years, published two books on the subject, and several monographs. “Various change management techniques will come and go,” Griffith suggests. “But by using contemporary computing power, Six Sigma allows for more careful analysis and more effective decision making, aiming for the optimal solution rather than what’s simply ‘good enough.’ It really takes traditional TQM efforts to the next level. Six Sigma principles have a great future in industry.”

Part Two to this examination of Six Sigma’s impact on managed care will appear in the December issue of MHE.

Ian R. Lazarus, FACHE and Keith Butler, M.D. are principals with Creato Performance Solutions (www.creato.com) which provides strategic advisory services, including Six Sigma Consulting, to industry providers and suppliers.