Exploiting Trends in Strategic Planning to Prepare for Reform

As appeared in The Journal of industry Management (Vol 56, No. 2), March/April 2011.

By Ian R. Lazarus, FACHE, Director, KP OnCall, LLC, and Senior Advisor, Creato

Let’s start with the question that is on everybody’s mind, but perhaps is not asked aloud because we don’t feel there is a reliable response. A question that embodies the uncertainty of our time. A question that, when sufficiently answered, may put an end to the paralysis felt by many in the industry industry. Quite simply: What will it take for industry executives, particularly those working on the provider side, to finally sleep well at night?

This question is, of course, a metaphor for the larger challenges facing our industry. As leaders of industry systems wait for clarity from recent reform legislation, important work is being delayed. Do leaders think the answer—the direction we ultimately need to follow—will come from our government? From consultants? From within?

When leaders realize that the answer lies within, they can begin to leverage their capacity for change. And given the magnitude of change that reform calls for over a relatively short period of time, it is no longer practical to rely on the typical long-range planning process that has become a tradition in industry circles. Indeed, industry executives must plan for many compressed cycles of planning and execution over the next three years.

Other fields give precedence to this shorter-cycle thinking. In the military, for example, the philosophy regarding strategy is that “no plan survives first contact.” Plans that are overly rigid will fail to allow for the course corrections that are necessary in an uncertain environment. “We will stick to our plan” may indeed become the famous last words of otherwise great leaders.

Therefore, if industry executives wish to feel a modicum of control over their destiny (recognizing that control is merely an illusion), they must commit to a discipline of planning and execution that will allow them to respond quickly to the changing landscape that lies ahead. Certainly this advice has been offered before. It also has been frequently ignored, which gives rise to the caution that it is not just the big company that acquires the small, it’s the fast that acquires the slow.

Given the importance of planning to a leader’s legacy, it is worthwhile to step back and look at emerging trends in strategic planning, and what an effective planning model looks like in contemporary business. Leaders can then assess their capacity to be effective as change agents or plug gaps that stand as an obstacle to their success.

EMERGING TREND 1 : LINKING STRATEGY TO PERFORMANCE IMPROVEMENT

We start with one of the most fundamental requirements of effective strategy execution—linking performance improvement (PI) efforts with the overall direction of the organization. As obvious as this may seem, many organizations still perform this work in silos; the board and senior management compose the plan, desired outcomes, and related metrics without any direct link to projects or PI initiatives that will deliver the results. Correspondingly, departments launch PI initiatives on their own without regarding the priority such projects might have in the context of strategy or even whether those opportunities will become obsolete before started given the strategic direction of the organization.

“Momentum toward achieving an organization’s strategic vision can only be maintained with a pervasive culture of continuous performance improvement,” cautions Rick Rawson, CEO at Adventist Central Valley Network in Hanford, California. “This is a commitment that begins with the Board and the integration of performance improvement into the strategic plan” (Rawson 2010).

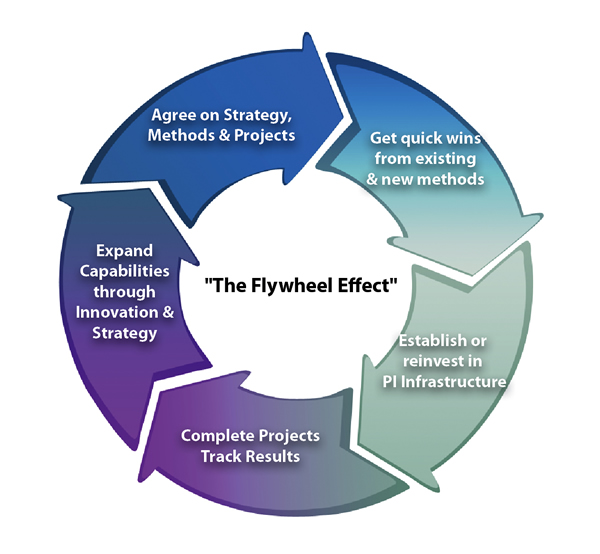

The “flywheel effect” described in Collins’ landmark book Good to Great (2001, 174-78) requires organizations to commit to a disciplined, iterative, and repetitive approach to improvement. This allows them to establish the powerful momentum that one observes when a heavy gear (or flywheel) moves with such speed that the energy it gives off grows exponentially over time. Organizations seeking to emulate the flywheel effect must embrace an integrated path between strategic work and related PI efforts, as Exhibit 1 on the next page shows.

The periodic strategic planning cycle must include, from the beginning, consideration of the organization’s capacity to improve. This consideration will depend on the methods available for performance improvement. If those methods are lacking, it’s time to commit to training or outside assistance. A governance function that includes a subset of senior management and PI leaders should be established, with strict criteria on what projects will be funded. One of those criteria should be that the project is linked to corporate strategy. An ROI target might also be established for the entire project portfolio; the organization might agree to fund projects with intangible returns if the overall portfolio delivers on the target. The focus on quick wins will improve the likelihood that new efforts gain traction; once proven, the organization can readily expand the workforce exposed to these methods. This has been a particularly effective approach in introducing the Lean and Six Sigma methodologies to otherwise parochial cultures in the hospital setting.

The most common gap in organizations is a lack of commitment to completing projects and tracking results. All too often we hear of organizations that celebrate prematurely, only to find that the performance regresses to its original baseline. “You are what you measure,” and therefore it’s critical that industry organizations adopt control charts and control plans to create visibility around their efforts.

The final stage in the periodic strategic planning cycle is to challenge the status quo by introducing new methods that will be decided on in tandem with the strategic planning process. This allows for the highest level of commitment to carry the organization forward, not just with vision, but with the tools to reach it. How frequently organizations move through these planning cycle steps will ultimately distinguish the “fast companies” from the slow.

EMERGING TREND 2: RECOGNIZING AND RESPECTING NEED FOR BOTH PI AND INNOVATION

The literature includes much about new and powerful methods in performance improvement, such as Lean and Six Sigma. However, the principles of Six Sigma have been in existence for nearly 100 years; the application of such statistical principles to the output from agricultural production has been credited with an exponentially improving yield with no additional investment (Lazarus and Butler 2001). “We were absolutely convinced before applying the Six Sigma framework that the only way to improve the cycle time for lab processing was to hire more people,” recalls Jerry Kolins, MD, FACHE, citing a contemporary application of the principles, “but in actuality we were able to experience greater throughput with no additional staff” (Lazarus and Novicoff 2004).

But Six Sigma has gotten a bad reputation among organizations that don’t deploy the methods properly or exhibit the patience and resolve necessary to introduce it, execute it, and monitor results. Six Sigma has also been accused of making organizations too insular (Hindo 2007). This may be the only legitimate criticism of a method that is, by definition, focused on fixing processes that are not functioning to the desired level of capacity.

How does the organization free itself from this potential insularity? The answer lies in the cycle itself and in the inevitable point at which the organization must turn to forms of innovation that can accommodate the impact of market forces. Innovation as a method can be practiced at the strategic level or the project level. Through innovative strategic planning methods such as Appreciative Inquiry, the organization takes a very inclusive approach to leverage creativity down to the front-line worker. At the project level, industry organizations are turning increasingly to computer simulation, design simulation, or Design for Six Sigma, a derivative of Six Sigma, to create what does not exist.

The biggest mistake an organization could make at the planning stage would be to dismiss Six Sigma because it does not, in itself, drive innovation. On the contrary, Lean and Six Sigma can create the capacity to allow innovation to succeed, and all will be necessary ingredients for organizations to prevail in the new era of reform.

EMERGING TREND 3: THE ARRIVAL OF “BLUE OCEAN” THINKING IN INDUSTRY

In 2005, the concept of a “blue ocean” was introduced to the industry by authors W. Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne. Blue ocean thinking is provocative because it demands its audience consider a different paradigm: that to create the most profitable presence in a market requires a quantum leap in buyer value while simultaneously achieving a significant reduction in the industry’s cost structure. Innovative business models like Netflix and iTunes come to mind when discussing successful blue ocean models, but aspects of the model also can be found in established industries, such as airlines, entertainment, and retail (Southwest, Cirque du Soleil, and IKEA, respectively, use blue ocean thinking).

What does all of this have to do with industry? To start, the Affordable Care Act is a game-changing event that will require industry executives to look at their market in a completely different manner. Market relationships—whether through accountable care organizations or other mechanisms—will offer blue ocean opportunities to fast-moving organizations. Detecting these opportunities may not be difficult for a CEO monitoring the external environment, but it can be exceedingly difficult for a management team, medical staff, or board that is skeptical of the need to change. And changing the current mode of delivery is precisely what is called for— in a way that will bring efficiencies to the consumption of industry services while lowering the industry’s overall cost structure.

More recently, hospitals have shared their own experiences with the application of blue ocean strategy to their planning process. “We are integrating blue ocean thinking as a way to positively frame the intentional disruption that we as an organization are driving through our improvement and innovation processes, and which is being driven externally by industry reform,” notes Mark Herzog, FACHE, CEO at Holy Family Health System in Manitowoc, WI. “Blue ocean thinking helps us envision an exciting, vibrant future of essentiality to the market and significance to our community” (Herzog 2010).

It’s obvious that no article, here or elsewhere, will offer a single answer on how to succeed as the most profound industry legislation of our generation takes effect. Fundamentally, leaders must lead, and doing so includes the ability to create a plan that allows for flexibility, drives the right performance improvement initiatives, and encourages innovation and willingness to look at the future as being quite different from the past. It will require leaders to redefine the fundamentals of planning and execution, and to do this in more compressed cycles. When leaders do this, they are certainly entitled to a good night’s sleep.

REFERENCES

Herzog, M. 2010. Interview with author, December 20.

Hindo, B. 2007. “At 3M, a Struggle Between Efficiency and Creativity.” Business Week June 11.

Kim, C. W., and R. Mauborgne. 2005. Blue Ocean Strategy: How to Create Uncontested Market Space and Make the Competition Irrelevant. Boston: Harvard Business Press.

Lazarus, I., and K. Butler. 2001. “The Promise of Six Sigma.” Managed healthcare Executive 11 (10).

Lazarus, I., and W. Novicoff. 2004. “Six Sigma Enters the industry Mainstream.” Managed healthcare Executive 14 (1).

Rawson, R. 2010. Interview with author, December 15.

Ian R. Lazarus, FACHE, is a Senior Advisor with Creato (www.creato.com).